The Effective Implementation Cohort (EIC) aims to increase districts’ capacity to implement a high-quality middle-grade (6-8) math curriculum to accelerate learning for students experiencing poverty, Black, Latino/a, and/or English Learner (EL)-Designated students. In this final report, we present findings from seven learning questions from the EIC. Across the seven learning questions, we describe:

1) findings from Year 3 of the study (Y3) in detail as related to the use of implementation strategies, district implementation factors, teacher perception, and student outcomes from both quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews/focus groups;

2) longitudinal trends;

3) key learnings related to best practices in implementation from across years;

4) main implementation challenges that were experienced within the EIC; and

5) how key learnings from the EIC relate to the broader implementation science literature.

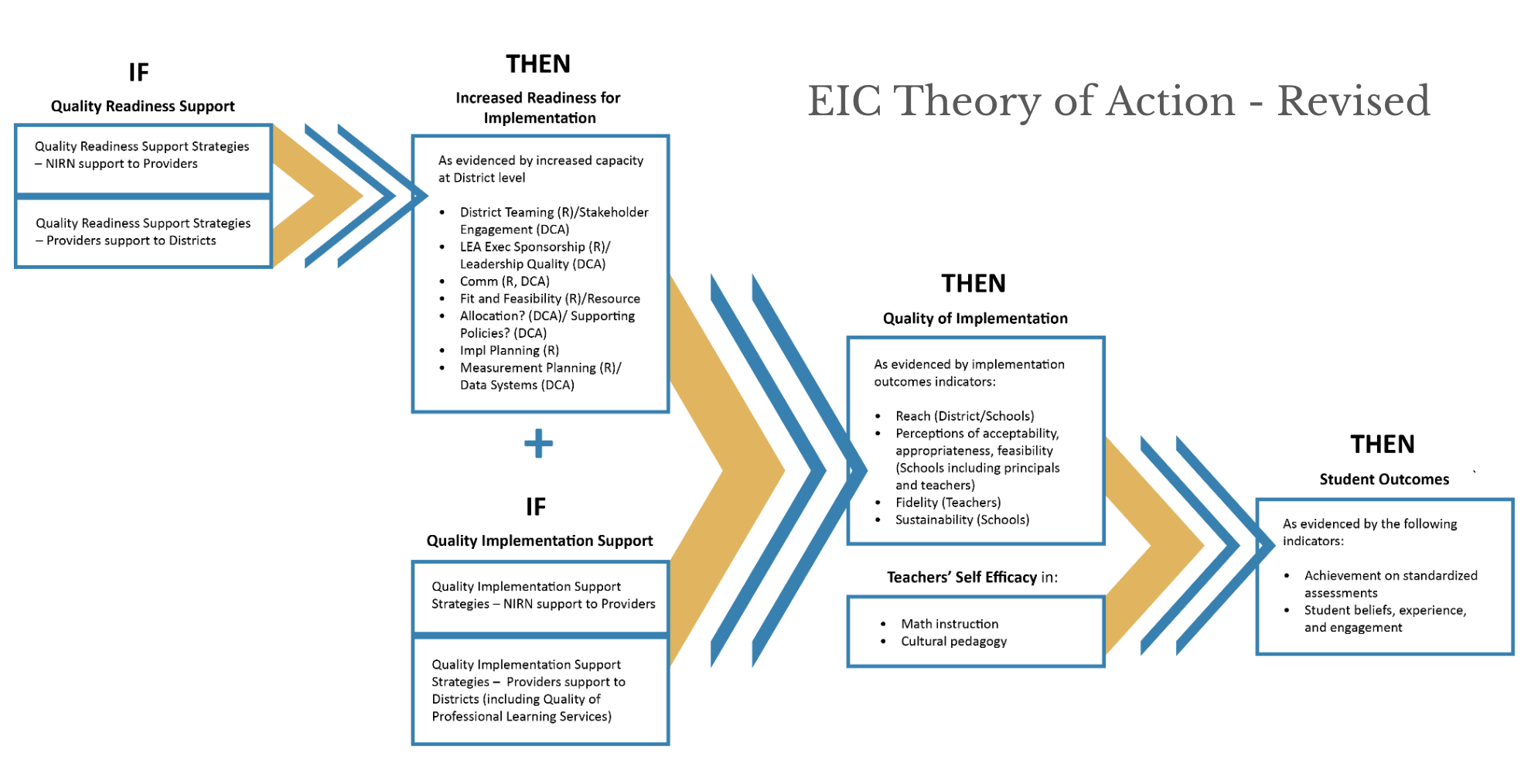

In this brief executive summary, key findings are synthesized across learning questions using the framing of the EIC Theory of Action (TOA). It examines how implementation impacts the system, from implementation strategies and their relation to district implementation outcomes, to the impact on teacher implementation perceptions and self-efficacy for instruction, to student outcomes.

Implementation Strategies and Their Relation to District Implementation Factors

The TOA posits that implementation strategies are key to impacting outcomes throughout the system. In the EIC, we examined seven key implementation strategy clusters: 1) Implementation Supports; 2) Program Integration; 3) Engagement of Program Recipients; 4) Cultivating Relationships; 5) Implementation Infrastructure; 6) Data; and 7) Financial Incentives.

In a survey, professional learning provider and local education agency (LEA) staff rated the quality and effectiveness of strategy clusters to be high throughout the cohort. Notably, the quality and effectiveness of strategies were highly correlated to increased capacity for implementation at the district level (district capacity, district teaming, and school leadership).

Qualitative findings suggested that best practices for implementation strategies required contextualization and tailoring of implementation supports. Any implementation strategy used in isolation was unlikely to be effective; rather, the most successful approach was to use a system-wide, multi-level, integrated package of strategies.

District Implementation Factors and Their Relation to Teacher Implementation Factors and Self-Efficacy

Within the TOA, higher district implementation scores (district capacity, district teaming, school leadership) should relate to higher scores for teachers’ implementation factors (e.g., perception of acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the curriculum) and self-efficacy (for math instruction, for cultural pedagogy). Findings suggested:

District capacity for implementation significantly grew across the years. Correlations showed that the relation between district capacity and district teaming got stronger each year.

Although most statistical relations were not significant because the small number of districts limited statistical power, both increased district capacity and increased district teaming over time trended positively with increases in most teacher factors (acceptability of the curriculum, appropriateness of the curriculum, self-efficacy for math instruction, and self-efficacy for cultural pedagogy, though relations were slightly negative for feasibility). Increased ratings of district teaming over time predicted increased district-average teacher self-efficacy for math instruction at a marginally significant level.

Teacher Implementation Factors and Self-Efficacy and Their Relation to Student Outcomes

In the TOA, higher ratings from teachers on implementation factors and self-efficacy was hypothesized to be associated with greater student outcomes. In general throughout the years, both teachers’ self-efficacy for math instruction and ratings of acceptability of the curriculum tended to be positively related to student outcomes. This was particularly evident in the deep dive sample that allowed for a more fine-grained analysis in which teachers could be directly linked to their own students.

Significant interactions in the deep dive sample emerged between acceptability and self-efficacy for math instruction that showed that teachers’ self-efficacy for math instruction was significantly positively linked to most student outcomes, including math engagement, growth mindset, math self-efficacy, and achievement, only when teachers also reported high acceptability of the curriculum. This means that even if teachers reported high self-efficacy for math instruction, if they did not like the curriculum, students did not show benefit from their teachers’ self-efficacy.

*Notably, this pattern did not emerge for math enjoyment.

Although other interactions were not significant, a consistent pattern of trends in the same direction for the same four student outcomes highlighted the interdependence of implementation factors on impacting student outcomes—students benefited more when their teachers had higher beliefs on more than one implementation factor (i.e., acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility) or self-efficacy variable.

Overall, teachers’ implementation factors had little additional impact on student outcomes beyond what was explained by student characteristics. The most notable, though still minor, effect was observed in student achievement (a small effect, f2 = .03). Interestingly, nearly half of the variation in student achievement (47.2%) was attributable to the factors shared among students grouped by teacher (including elements not directly studied, e.g., instructional practice, environmental characteristics, and more). In contrast, math beliefs and experiences were primarily at the individual student level, with less than 10% of their variance attributable to shared teacher factors. This suggests factors shared among students grouped by teacher have a large impact within an academic year on achievement, but a lower impact on math beliefs and experiences.

Student Demographics, Their Relation to Student Outcomes, and the Differential Impact of Teacher Factors

Of those individual student differences, demographics remained significant predictors of student outcomes in Y3.

General trends suggested that White students tended to report higher levels of math beliefs and experiences, and scored higher on state end-of-year math assessments, than other racial groups.

However, the opposite emerged for math enjoyment, such that both Hispanic and Black students reported higher enjoyment of math than White students.

Furthermore, students who were not English Learners generally reported higher levels of math beliefs and experiences than their English Learner peers, and scored higher on state end-of-year math tests.

However, significant interactions also emerged between teacher implementation factors and student outcomes; this demonstrates that teacher factors can differentially impact various student demographic groups, which highlights the importance of taking the needs of priority students into account when planning an implementation effort.

Lessons Learned for Scaling

Successfully implementing and scaling educational initiatives requires careful attention to several key factors. The EIC sheds light on eight crucial lessons that contribute to setting a path to successful implementation and desirable outcomes for our partners and the students they serve. These include the critical role of context and readiness and ensuring fidelity with relevant adaptations to maintain the integrity of the innovations (i.e., math practices, curriculum) while allowing for necessary adjustments; emphasizing cultural relevancy to ensure innovations resonate with diverse populations and contexts; and highlighting capacity building through implementation supports, such as professional development.

The importance of data is paramount for continuous improvement, as is adopting a systems approach with linked teams to foster cohesive efforts. Finally, we advocate for the use of multi-level, integrated implementation strategies and stress the vital importance of involving critical perspectives, particularly students and their families, to ensure initiatives are truly responsive and sustainable. For each of these lessons, we will first discuss relevant literature, followed by an explanation of its operationalization within the EIC project, and conclude with why this lesson learned is important for scaling.

The information provided throughout this report cites multiple studies. For a complete list of references, please refer to the list below.